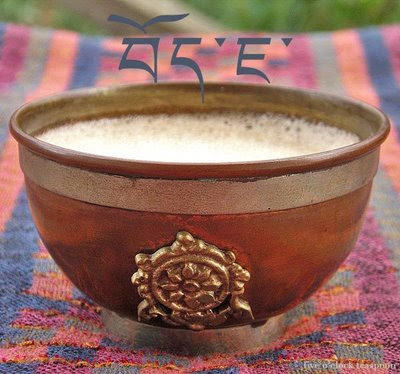

I first tasted butter tea on a blustery spring day at Tsampa, a Tibetan restaurant on E. 9th St in New York City, named after the barley flour prevalent in Tibetan cooking. Although some people find its intense saltiness an acquired taste, butter tea, known as bo ja, is instantly warming and satisfying, with a rich and intriguing flavor. In Tibet, the drink is made by heating a portion of compressed tea in boiling water for up to 15 minutes. The liquid is then strained and yak butter, salt, and if desired, milk, are added. Traditionally, the brew is poured into a wooden cylinder called a dogmo and churned until frothy.

A group of Tibetan bells.

A group of Tibetan bells.In Tibet, butter tea is always served as a gesture of hospitality, and consumed throughout the day. The drink is not only found in Tibet, however, and is widely consumed in other areas of the Himalayas such as Bhutan and Mongolia as it provides essential vitamins and antioxidants, thereby offering sustenance and fortifying strength in the harsh mountain conditions. Butter tea is also known in China, particularly in areas that border Tibet, such as Sichuan. In fact, butter tea recipes are recorded in Chinese publications dating to the Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) eras (H.T. Huang, Science and Civilisation in China, v. VI: 5 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.). While Tibetan butter tea has a very different character from Chinese tea, it is actually closely related to early Chinese tea drinking practices of the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) periods.

Perhaps the first large-scale introduction of Chinese tea drinking practices to Tibet began in the Tang dynasty, when Emperor Taizong sent his daughter, Princess Wencheng to marry the Tibetan King Songzan Gambo, in the middle of the 7th century. During the Tang dynasty, tea was commonly prepared with salt in China. In his treatise Chajing (Classic of Tea), Lu Yu, the 8th century tea scholar, details the procedure for roasting and grinding tea cakes into a powder to which boiled water was added. Salt was spooned into the water as it boiled. Lu Yu also lists a porcelain salt cellar among the accoutrements necessary for tea preparation. When Princess Wencheng travelled to Tibet, she brought the arts of the Chinese court with her. Craftsmen skilled in areas from calligraphy, tea ceremony, and textile production, to metalsmithing and agriculture, brought their materials, expertise, and techniques to Tibet. In this way the elite Tang mode of tea drinking was transmitted to the Tibetan court.

Later in the Song dynasty, another wave of Chinese tea culture reached Tibet. During this period, China began trading silk and silver with Tibet in exchange for the robust Tibetan horses needed for China's military. As this system became economically unfeasible for the Chinese, they eventually traded salt certificates for horses instead. Tibetan traders could easily redeem these for commodities, such as tea, in Sichuan markets. Chinese tea, sold in compressed brick form, became very popular in Tibet. China strictly guarded its monopoly of the tea industry, however, instituting punishments for those caught selling tea seeds and shoots to Tibet. (Paul J. Smith, Taxing Heaven's Storehouse: Horses, Bureaucrats, and the Destruction of the Sichuan Tea Industry, 1074-1224 Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991).

By the Song period, little had changed in the Chinese tea making process, except that the final infusion was whisked to create a thick foam. The spumy surface was a point of aesthetic appreciation, believed to contain the tea's essence. Although among the Chinese elite tea was no longer made with salt, both the practice of salting and foaming tea are hallmarks of Tibetan-style tea. While it is likely that the Tibetan way of preparing tea was inspired by the Tang and Song Chinese methods, butter tea is uniquely suited to the Tibetan lifestyle, bracing the body and tempering a meat-rich diet with the concentrated nutrients of the tea plant.

Tibetan Butter Tea

Serves 1

Follow the proportions below to multiply the number of servings

Ingredients:

1 rounded tsp dark Chinese tea, preferably pu' er

1 cup water

1 Tbs butter

1/4 cup whole milk or cream (optional)

1/4 tsp salt

1. Bring water to the boil and add tea. Simmer about 8-15 minutes.

2. Strain leaves and return brewed tea to the pot. Add butter, salt, (and milk if using) to the tea. Mix with an immersion blender until frothy.

3. Pour into cup and serve with something sweet.