Although there have been few scholarly publications devoted to representations of food in literature, the subject has begun to receive greater attention in recent years. Children's literature offers a particularly interesting focus, for in stories of make-believe, food may be conjured in infinite variety. In many examples of such works, food bridges the fantastic and the quotidian- a banal ritual in an extraordinary manifestation. Food frequently provides the medium through which a character enters an elusive world, often occupied by talking animals, mythical beasts, and ambulatory objects. These foodscapes of the imagination become the entrance to marvelous adventures.

In Alice and Wonderland, for instance, after falling down a rabbit hole, Alice encounters a bottle marked 'Drink Me' and a cake marked 'Eat Me' which, after ingesting, cause her body to in turn shrink and then grow rapidly, hinting at the absurdites to follow. As in other tales and fables such as that of Hansel and Gretel, food is the conduit through which characters undergo a physical and/or mental transformation that translates their ordinary corporeality into the fantasy world.

In The Emerald City of Oz (1910), the sixth book in L. Frank Baum's chronicle of the Land of Oz, Chapter 16, "How Dorothy Visited Utensia," brings the main character, Dorothy, to the Kingdom of Utensia while traveling through the landscapes of Oz. Captured by a brigade of spoons, Dorothy, her dog Toto, and the yellow hen Billina, are taken to a land with a population made up entirely of kitchen utensils, ruled by King Kleaver. As the king and his subjects try to determine what to do with the prisoners, Dorothy is introduced to the various utensils around her. There is, for instance, the High Priest Colander, titled so because "He's the holiest thing we have in the kingdom" and the pepperbox, Mr. Piquant, who brashly condemns Dorothy to be killed three times, to which King Kleaver tempers with "Your remarks are piquant and highly-seasoned, but you need a scattering of commonsense. It is only necessary to kill a person once to make him dead; but I do not see that it is necessary to kill this little girl at all."

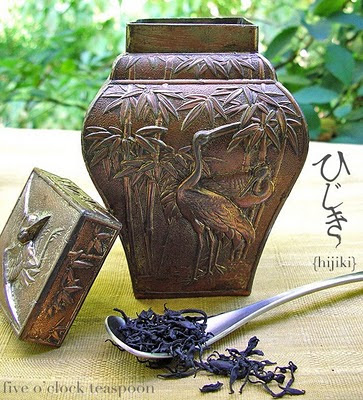

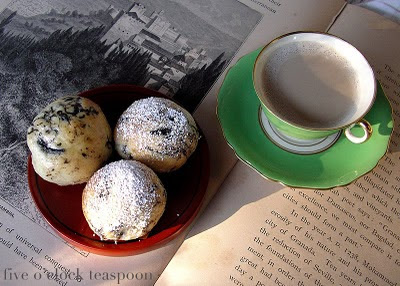

As the utensils disagree about Dorothy's predicament, each reveals a mirthful license. The corkscrew tries to weigh in, stating "I'm a lawyer...I am accustomed to appear at the bar" and the flatiron attempts to "smooth this thing over." Curiously, Utensia is characterized by an absence of food, perhaps explaining the boredom felt by the captain of the spoons brigade, charging that in capturing Dorothy he intended "To create some excitement...It is so quiet here that we are all getting rusty for want of amusement. For my part, I prefer to see stirring times." After Dorothy, Toto, and Billina are released and permitted to leave, they go into the forest to pick blackberries, for Dorothy is hungry and according to King Kleaver, "There isn't a morsel to eat in all Utensia, that I know of."

Despite, or because of its lack of food, Utensia is very much about the food that is not there. Although the utensils can move and talk, they are unable to prepare food, suggesting that it is their inability to cook that most strikingly separates them from the human world. Indeed, without their comestible partners the cookware and utensils are without purpose and somewhat forlorn. The flatiron reminds everyone, "We are supposed to be useful to mankind, you know." Hence, it is the idea of food and its preparation that engages the reader. The image of food itself is left to the reader's imagination.

As the utensils disagree about Dorothy's predicament, each reveals a mirthful license. The corkscrew tries to weigh in, stating "I'm a lawyer...I am accustomed to appear at the bar" and the flatiron attempts to "smooth this thing over." Curiously, Utensia is characterized by an absence of food, perhaps explaining the boredom felt by the captain of the spoons brigade, charging that in capturing Dorothy he intended "To create some excitement...It is so quiet here that we are all getting rusty for want of amusement. For my part, I prefer to see stirring times." After Dorothy, Toto, and Billina are released and permitted to leave, they go into the forest to pick blackberries, for Dorothy is hungry and according to King Kleaver, "There isn't a morsel to eat in all Utensia, that I know of."

Despite, or because of its lack of food, Utensia is very much about the food that is not there. Although the utensils can move and talk, they are unable to prepare food, suggesting that it is their inability to cook that most strikingly separates them from the human world. Indeed, without their comestible partners the cookware and utensils are without purpose and somewhat forlorn. The flatiron reminds everyone, "We are supposed to be useful to mankind, you know." Hence, it is the idea of food and its preparation that engages the reader. The image of food itself is left to the reader's imagination.

Coming soon...more foodscapes in Oz and beyond.

Part II: Bunbury

Part III: Raggedy Ann and the Magic Wishing Pebble

Part IV: Raggedy Ann in Cookie Land

Part II: Bunbury

Part III: Raggedy Ann and the Magic Wishing Pebble

Part IV: Raggedy Ann in Cookie Land